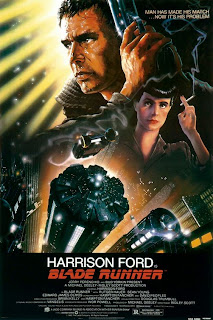

On Monday I treated myself to a ticket to see the new release of Blade Runner: The Final Cut at the Rio. I was reminded of how fun it is to go to the cinema alone, something I used to do a lot whilst at Cambridge, but got out of the habit once in London sheerly because of the expense of cinema tickets. However as the Rio does £5 student tickets on Mondays, maybe I'll get back into the habit. The great thing about solitary cinema is you don't have to worry about what the other person thinks; whether they're enjoying it as much (or as little) as you are; whether you made an error in choosing the film. You can just sit selfishly back and experience the film for what it is, distractionless.

On Monday I treated myself to a ticket to see the new release of Blade Runner: The Final Cut at the Rio. I was reminded of how fun it is to go to the cinema alone, something I used to do a lot whilst at Cambridge, but got out of the habit once in London sheerly because of the expense of cinema tickets. However as the Rio does £5 student tickets on Mondays, maybe I'll get back into the habit. The great thing about solitary cinema is you don't have to worry about what the other person thinks; whether they're enjoying it as much (or as little) as you are; whether you made an error in choosing the film. You can just sit selfishly back and experience the film for what it is, distractionless.

At Monday's screening, just being in the cinema felt special. Once the trailers had finished, as the curtains trailed open to a black screen and the title credits appeared, a collective thrill ran through the audience like quicksilver. I think it's because we were all there as fans of the original film. We knew something good was coming. The theatre was almost full, mainly with young people in their twenties and thirties; gangs of sci-fi geeks, cult film buffs, the slightly intimidating dalstonite fashiontellectuals, and the odd person who might have even seen the original in a cinema rather than on their parent’s VCR.

The film’s Vangelis-scored soundtrack is incredible. Sitting in the blackness and feeling the waves of plangent chords wash over you is shiver-inspiring; like getting into a miner’s lift, watching the mesh shutters close and feeling yourself descend into the dark middle of the earth - you feel even before Blade Runner begins that this film is going to take you places, show you things that are new and dark and important.

It is stylish like too few movies dare to be today. Of course it takes a gutsy director with a capacious imagination to make something this coherent in vision. You also need a razor-sharp narrative focus, something that Ridley Scott managed to carve from the ingenious but multi-threaded novel that the film is based on: “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” by Philip K. Dick, written in 1968. In that, we engage with a number of characters, each with their own claims on our affection; in Blade Runner there is really only room for one protagonist and that is Harrison Ford’s morose yet likeable Rick Deckard.

And in a way, that’s cleaner, clearer. Like one of my journalism tutors says: “Once you’re on the M1, stay on the M1” - so, to keep your audience's attention, don’t go off on any slip-roads, just cleave to one story. Scott manages that perfectly: there’s no crossing of wires here, no distracting slip-roads into the religion or drugs themes that add breadth but also complicate the novel. Occasionally themes are gestured at that would have been better left out - when Ford's Deckard notes that the owl in the Tyrell Corporation offices is a fake, it's an observation loaded with meaning in the novel, yet somehow empty in the film, where the idea that all animals are now virtually extinct is never stated or explored.

Where the film exceeds the book is - perhaps predictably - in its visual evoking of a dystopian future. The story is set in ‘L.A., 2019’, but it’s a gloriously Chinesified L.A. with street stalls selling noodles, signs in Mandarin and kimonos everywhere; clearly the filmmakers foresaw China's global dominance even in 1982. The other overriding influence is film noir: Rick Deckard is the future's Philip Marlowe, a hard-drinking, raincoat-wearing gumshoe except he carries a gun that can blast robots through glass, rather than the 9mm luger pistol preferred by Marlowe, and he travels around in jet-propelled flying cars. Aside from that, Deckard fits perfectly into the film noir tradition, traversing rain-slicked streets with collar up, falling for femme fatales and sustaining bruises to body and ego in the course of his work. His job is to 'retire' the Nexus 6 replicants - androids - that have escaped their slavery 'off-world' and are hiding somewhere in this always-night, neon-lit L.A.

The other overriding influence is film noir: Rick Deckard is the future's Philip Marlowe, a hard-drinking, raincoat-wearing gumshoe except he carries a gun that can blast robots through glass, rather than the 9mm luger pistol preferred by Marlowe, and he travels around in jet-propelled flying cars. Aside from that, Deckard fits perfectly into the film noir tradition, traversing rain-slicked streets with collar up, falling for femme fatales and sustaining bruises to body and ego in the course of his work. His job is to 'retire' the Nexus 6 replicants - androids - that have escaped their slavery 'off-world' and are hiding somewhere in this always-night, neon-lit L.A.

These replicants are at once terrifying and pitiful; living in constant fear for their lives, capable of developing emotional connections with each other and more than conscious of the rare preciousness of life, yet also merciless and hideously violent. Rutger Hauer's performance is so compelling as to almost outshine Ford, though in fact they complement each other perfectly - Hauer intense, aggressive, everything externalized, speaking in near-poetry; Ford all wordless longing and internal conflict.  The only jarring moment in the film is the scene where Deckard seduces Rachel, a replicant who has been implanted with false memories to make her believe she is human. Why does their romance begin with what looks very much like rape? There must be some carefully thought out logic to it but despite searching online discussion boards I haven't yet found a legible answer.

The only jarring moment in the film is the scene where Deckard seduces Rachel, a replicant who has been implanted with false memories to make her believe she is human. Why does their romance begin with what looks very much like rape? There must be some carefully thought out logic to it but despite searching online discussion boards I haven't yet found a legible answer.

Despite that, the film is still a masterpiece and has informed many movies since; its influence can be traced in Minority Report, the Terminator films, 12 Monkeys and Christopher Nolan's Batman Begins to name but a few. Catch it in the cinema while you can.

Wednesday, 19 December 2007

Blade Running

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment