In 2002, a species of moth never previously recorded in north-western Europe landed in Sean Clancy's garden in Kent, England. It would become known as "Clancy's Rustic", and by 2005, dozens were being recorded on the English coast. Meanwhile, in a cliff-top garden at one of the most southerly points of England, Britain's Centre for Ecology & Hydrology had been tracking insect migration since 1982. Their results were startling. Hordes of rare butterflies and moths (lepidoptera), once found only in the Mediterranean and North Africa, were venturing into Northern Europe in unprecedented numbers. In January, Tim Sparks and his team finally published their findings: over 25 years, new species of lepidoptera entering Britain had increased by a staggering 400%. Sparks says the cause is clear: global warming. Just as Al Gore called the melting of the polar ice-caps "the canary in the coal mine", the new itineraries of migrating insects are a bright yellow warning - tangible proof the world’s natural order is undergoing radical change. As the earth warms, with butterflies already on the move, could people be far behind? "There’s little we can do to control immigration of new insect species," says Sparks. "And unless climate change is moderated, it’s likely to displace large numbers of humans migrants in a similarly uncontrolled manner."

Climate-induced migration isn’t new; it’s a survival mechanism as old as life on earth. Human mobility helped cultures sidestep possible extinction, and often worked as a catalyst for growth and evolution. It could conceivably bring dividends again, but not without cost. The Earth Policy Institute in Washington estimates that 250,000 residents displaced by Hurricane Katrina have established homes elsewhere - and will never return to New Orleans. In December, the worst Bolivian floods in 25 years submerged an area the size of Britain, making 77,000 families homeless. “Environmental refugees could become one of the foremost human crises of our time” is the grim warning of Norman Myers, an Oxford University environmental scientist who has been investigating the phenomenon for 15 years.

When Myers first wrote about the new breed of “environmental refugees” in 1995, he was dismissed as a hysteric. He certainly painted a scary scenario: 200 million environmental refugees by 2050, equivalent to two-thirds of the population of the United States; “a massive crisis; famine and starvation.” But the tide has changed, and his apocalyptic vision - “This is a major new phenomenon and it’s growing much worse, very rapidly” - looks increasingly plausible. British geographer Richard Black, who once suggested the concept of environmental refugees was nothing but a “myth,” now acknowledges, “There’s no question that one of the consequences of climate change will be an increase in migration… New research has been published, and I’d like to think I have a more sophisticated view on it.” Black is a world expert on migration, and a contributing author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s landmark report on the impacts of global warming, released yesterday. His concession, therefore, is significant.

But while the likelihood of mass climate migration is now acknowledged, there’s still an unnerving lack of consensus on what one of the broadest impacts of global warming might actually look like. All the experts agree serious research is required, and urgently. Richard Black concedes, “We don’t have any adequate data source for understanding this. Not one.” Myers, who found it difficult to obtain funding for his research, is first to admit: “I’ve done little research since 1995, so I just don’t know whether the figures have changed. Nobody’s doing on-the-ground analysis.”

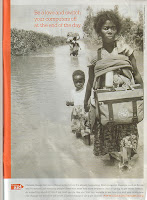

What is lamentably clear is that the biggest losers will be those already most vulnerable: the developing world. Impoverished and climate-sensitive nations like Bangladesh and Kenya simply don’t have the resources to provide relief for displaced residents, and are desperately low on cash for the construction projects that could limit future damage. In 1996 Myers estimated that sea level rises induced by global warming would threaten the lives of 26 million people in Bangladesh, 73 million in China and 20 million in India. It’s from these areas that “climate refugees” are most likely to emerge, alongside drought-stricken regions of Africa. In the Mandera district of North-East Kenya, a four-fold increase of drought has already forced half a million pastoral farmers to abandon their way of life. In the village of Libehiya, houses are buried in sand dunes. This, according to a Christian Aid study last year, is “the climate change frontline”.

Where will climate refugees go? Black suggests European policymakers who imagine millions of new asylum-seekers probably have it wrong: “I suspect worsening climate won’t dramatically increase the number of West Africans coming to Europe. It will just increase the number of poor and destitute West Africans. The more desperate your circumstances, the more difficult it is to put together the money for a long journey. If you’re an impoverished farmer affected by a natural disaster you don’t just think, ‘Oh I know, I’ll go to Paris’. These people are living on a dollar a day; they don’t have a few thousand dollars stashed under their beds.”

The biggest losers will be those who never manage to earn the official title of “refugee” and are thus ineligible for international aid. As yet, there's no official recognition that environmental problems could alone justify “refugee” status. Myers complains the UN won’t rewrite the rules, “because their budgets are already overstrained, and they’re worried they’ll be swamped. Yet these are people whose governments are unable to safeguard their lives.” A UNHCR spokesman told me that although “we’re aware of it and it’s certainly an issue to watch,” the world’s pre-eminent refugee agency has no current strategy to deal with the threat.

The developed world will of course have its own share of losers. In 2003, a heat wave in Europe killed over 21,000 people across five countries. The IPCC warns that such sweltering heat will become increasingly common, with higher maximum temperatures and an average rise of between 1.1 and 6.4 degrees C over the next century.

Will this create “climate refugees”? Talking to experts like Myers and Black, it seems the answer pivots on a population’s “adaptive capacity”; crucially, inhabitants in the West can adapt more easily than people in poorer, less developed economies. France was able to spend an extra $748 million on hospital emergency services during the 2003 heat wave, later developing a four-stage plan canicule (for the so-called “dog days” from early July to early September). The Netherlands, after a 1953 flood killed nearly 2,000 people and evacuated 70,000, spent $8 billion over 25 years to prevent a recurrence; they now have a ministry devoted solely to the prevention of flooding - a department much consulted by U.S. specialists post-Katrina. Even supposing some people are forced to move, skilled and wealthy Westerners are less likely to become “refugees”, so much as “migrants” who are able to adapt, find work and rebuild their lives even if their home is destroyed.

Enter the winners. While areas like southern Europe will become increasingly uncomfortable weather-wise, there could be capital gains for the more temperate north. The Scottish government is sponsoring “Highland 2007,” a campaign to promote the Highlands as a desirable place to live. It’s an effort to arrest a declining population, but such marketing could become unnecessary if forest fires, heat waves and water shortages encourage northwards relocation from Spain, Italy and southern France. Underpopulated areas like Sweden - a country the size of California with a population of 8 million - not to mention Norway and Finland, could reap the rewards of an influx of skilled workers. And as urban heat islands like London, Paris and Tokyo turn airless and muggy, internal migration could usefully redistribute population from cities to the country.

Archaeologist Arlene Rosen from University College London is convinced there will be another category of winners too. She’s just written a book called “Civilizing Climate”. “Certain ancient societies adapted to climate change. For every society that collapsed, there was one next door that survived and got stronger because of it.” Rosen points to the first state society in China in 1900 - 1500 B.C., where incredible drought was nevertheless accompanied by a period of growth and expanding social organization. Archaeologists believe difficult climatic conditions led directly to an increase in trade, which created an economic upswing across society. And for around 5000 years, the Sahara was a green and fertile area, until it began to dry up in 4000 B.C., causing the large-scale migration of people to the Nile region, a key step in the creation of Egyptian civilization. “Humans are a resilient species,” says Rosen.

She believes history has lessons to impart, if we care enough to listen. “The bottom line we get from studying societies that survived climate change is that it’s in everybody’s best interest to share resources between the winners and the losers." Rosen says. "Political and economic cooperation to move goods and services around is vital. Wealthy governments today need to be convinced that it’s in their own interests to help the developing world.” Myers believes action on climate refugees could define our future. “Ten years ago I wrote a book-length report on this, I gave lectures, I talked to policy leaders and politicians. The global community just turned its back.” With climate change finally a priority on the international agenda, the experts hope the time has come for environmental refugees to get the attention they deserve. Perhaps we can then confront the brave new migratory world with foresight, not just fear.

Sunday, 8 April 2007

Climate Refugees

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment